Gerüchte, German for „rumors“. This is the word the three authors chose to begin an article dated August 31, 2022. Rumors is maybe the word that best describes the content of this article. In the print version of the weekly newspaper Die Zeit, the word is placed in such a way that the first letter, the G, is spread out over seven lines.

The article has severely damaged the career of Berlin gallery owner Johann König. Under the headline "I yelled at him and insulted him to make him go away“, the article accuses the 41-year-old of abuse and makes strong accusations against König: it claims that the gallery owner misbehaved at parties and harassed women. It is about grabbing and involuntary kissing, touching a back.

The accusations are based on statements by ten women, most of whom remain anonymous, who have submitted affidavits to the three authors of the article - Luisa Hommerich, Anne Kunze and Carolin Würfel. According to their article, the things König is accused of are said to have largely taken place in 2017. As of today, no legal proceedings are underway against him. In pure legal terms, König is an innocent man. What's more, König's legal objections to the article have been partially upheld by a court in Hamburg. In the online publication of Die Zeit, important passages had to be subsequently deleted because they could not be accounted for by the authors.

Internationally, the damage has already been done. Several media in Europe and the U.S. reported on the case with reference to Die Zeit. As an inquiry by the Berliner Zeitung to the responsible public prosecutor's office reveals, there had been two investigations against König, neither of which had resulted in sufficient cause for action. None of the matters involved sexual abuse, a spokesman for the public prosecutor's office said.

Nevertheless, the facts could not prevent König's name from now being associated with a "sex scandal". The accusations in detail usually play a subordinate role. Der Spiegel reported online that female employees of Königs gallery were affected, which was an unproven allegation and has since been deleted. The Art Newspaper still reports today that König "harassed ten women," which not even the Zeit article claims. The authors had "talked to ten women."

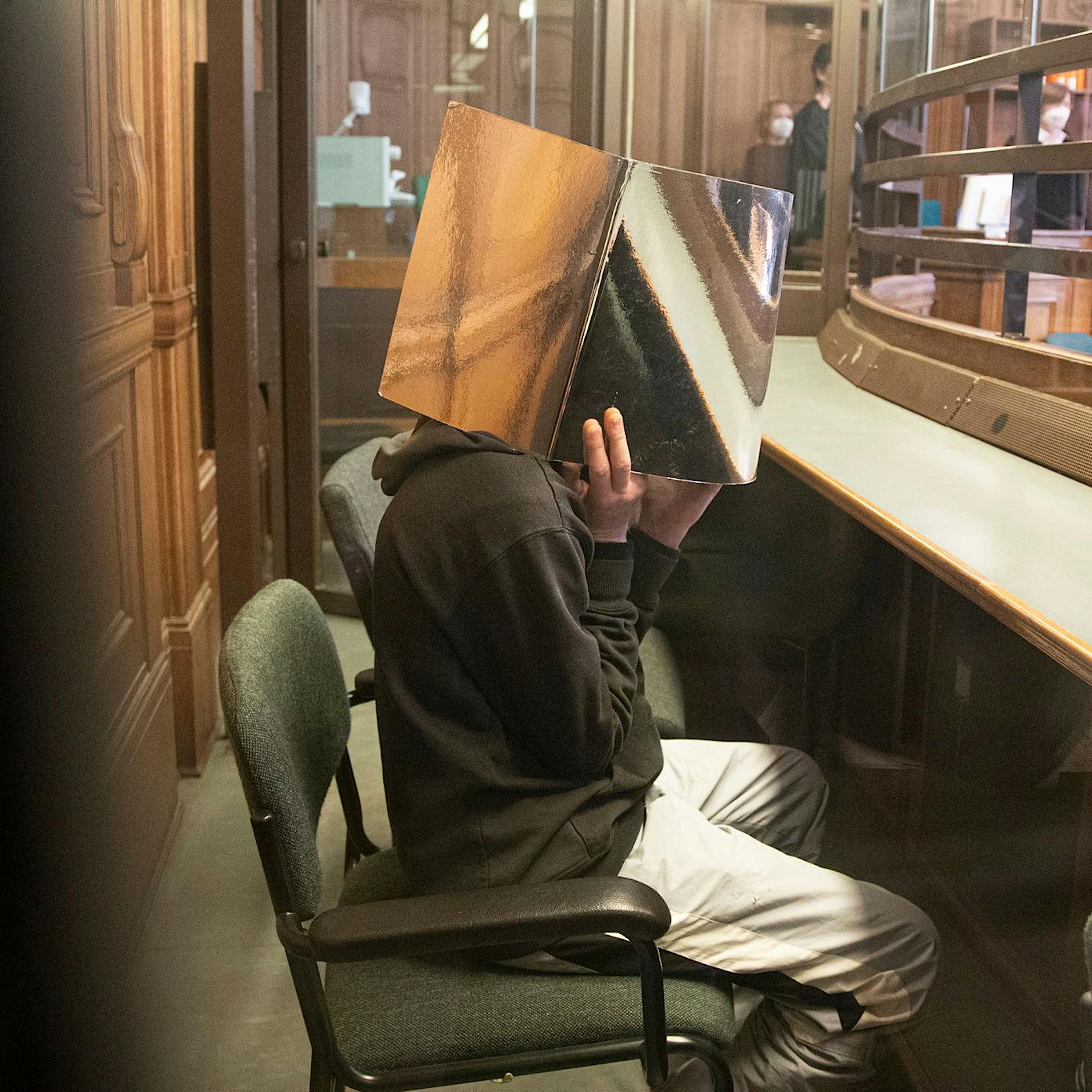

Guilty without trial

One could say: König was found guilty without a trial. This was probably also the aim of the Zeit article, whose authors were sure of König's unrestricted guilt and seem to be convinced of it to this day, as a reply suggests from the Zeit press office.

However, if one looks at the puzzle pieces of the Zeit investigation with distance, a picture emerges that is more complex and, among other things, tells us about current journalism — activist journalism of the kind that has been cultivated in some of Germany's editorial offices for some time. There are activists who claim that the legal concepts of today are based on patriarchal structures, that justice is not possible within them. Especially in cases of abuse of power or sexual harassment, guilt often cannot be proven legally, in the end it is testimony against testimony. Because of the presumption of innocence, it always amounts to an acquittal, in dubio pro reo - for the activists, this is only a legal trick for perpetrators to wash their hands of the matter.

Suspicion reporting, which is also what the König case is about, is therefore often considered among activists to be the last weapon of those affected. But what if the suspicion in a report turns out to be exaggerated, perhaps even false? In the case of comedian Luke Mockridge, for example, there are justified doubts about the reporting, in the #LinkeMeToo or Thomas Oberender cases as well - and now with Johann König. The media reports in these cases often seem like a kind of vigilante justice, following the motto: „When injustice becomes the law, resistance becomes a duty“. The consequence: In the fight for more justice, traditional rules of journalism are suspended.

In the case of König, it becomes apparent that the readers of the Zeit article were presented with a truncated picture. Research by Berliner Zeitung leads to the conclusion that this report should never have been published in this way. There are compliance conflicts between one of the authors and an editor of Die Zeit. The article seems one-sidedly researched — and on top of that, there is a draft script for a Netflix-style series. The script also deals with the König case and reads like a manual for activism, written by an author of the very same Zeit article. According to an anonymous source, it was written before the publication of the article and has, so to speak, prejudiced the subsequent research–anticipating a guilty verdict.

A manual for activist journalism

But let's take one step at a time. The case of Johann König begins in 2017. In the autumn, the first MeToo cases become known. Suddenly, abuse is also being discussed in Germany. In October 2017, an article by journalist Carolin Würfel appears on Zeit Online. The article causes a stir in the editorial ranks and makes her known in the journalism and activist scene. It describes the justified frustration that certain cases from the gray area of assault never lead to charges being filed or to a conviction of the perpetrators. This article also reads like a manual for activist journalism. It is a declaration of war against the Berlin „cultural elite“. It's headlined "Wir wissen es", German for: "We know it."

The author writes about a group of women who have collected names of men. It is a threat. While no names are mentioned, Würfel speaks specifically of ten men whose behavior she denounces: from the "restaurateur who trades cocaine for oral sex" to the "editor who harasses women who don't want to sleep with him." She ends with: "You know who you are."

Würfel's article polarizes and divides the editorial board. Court reporter and deputy editor-in-chief of Die Zeit Sabine Rückert writes a riposte two days later. As a response to an in-house article, Rückert's riposte is unusually harshly written. She asks: "Is blackmail and character assassination now a new kind of journalism?" She suggested Würfel and responsible editors had "suspended basic rules of journalism for showmanship". Rückert considers Würfel's article "activism“ and concludes with a warning: "You don't play tricks with law enforcement." It looks like a clash between two legal views, two generations of female journalists.

2017 is also the year of the parties that play a role in the Zeit article. The Berliner Zeitung has seen both the affidavits of the witnesses from the later Zeit report and König's answers to each of the facts of the case. Anyone who reads them will at least get a more differentiated picture of the events of those nights than from the article itself. They are not an acquittal of König, but neither are they a clear verdict of guilt. There is much to suggest that König behaved wrongly toward women. But to what extent? In what form? The gallery owner König stated in a letter that the events of 2017 "definitely did not take place in the manner described." He could sometimes be dissolute and impulsive, he said, but never acted intentionally in those moments, never kissed anyone against their will, never disrespected a rejection, ignored a no. However, if he had offended someone, he offered his apologies.

Around 2019, Johann König bought a work of art by the East German artist Wilhelm Klotzek, about whom Carolin Würfel had published a review in Die Zeit, for 9,000 euros. König bought it at the gallery of Alfons Klosterfelde, Würfel's husband, and sold it two years later for 25,000 euros. In the art market, that means he "flipped" the work. It is this flipping, people in the art market say, that made König so rich, successful, and so unpopular with many. Conversely, this means that there was an indirect conflict of interest.

In the art world, everything depends on image

The art market is a special market. A lot is paid in cash, a lot goes through contacts. The name of a gallery can make or break an artist. The simple appearance of a well-known person at an opening or a newspaper article can suddenly raise the value of the location, the artworks, the artist considerably. Everything depends on image.

Who is the team of authors approaching this topic? When the Zeit journalists confront Johann König at the end of August, they do not reveal themselves as a trio. Only two female Zeit employees sent König a catalog of 17 questions, only two showed up for an interview. Only when the finished article appeared in print did the name of the third author appear: Carolin Würfel.

In response to an inquiry from the Berliner Zeitung to Zeit's editor-in-chief, a spokeswoman says: "The research was conducted in Zeit's investigative department, to which Carolin Würfel does not belong. Ms. Würfel was involved in some, but not all, of the research interviews as a freelancer. She neither wrote the article nor was she present during its production." So why is Würfel in the byline? Why does she even feature in and call herself "an author of the article"? It doesn't add up.

This is shady behaviour on the one hand and problematic on the other, because Würfel is very well connected in the art world, has known Johann König for a long time - and, as mentioned, is married to the Berlin gallery owner Alfons Klosterfelde, a competitor of König. But this is not mentioned in the article, nor was it a problem for Die Zeit. According to a statement by Zeit, the couple is currently separated. Würfel herself did not comment when asked.

Why has the art scene reacted so quietly to Die Zeit's article? Some are silent because they don't want to mess with Johann König and his well-known media lawyers; others because Die Zeit is a powerful weekly newspaper, publishes the traditional art magazine Weltkunst, and publisher Florian Illies is also very well connected in the art world; thirdly, there are certainly also those who are secretly happy to see the fall of Johann König, one of their biggest, no, the biggest competitor in Berlin.

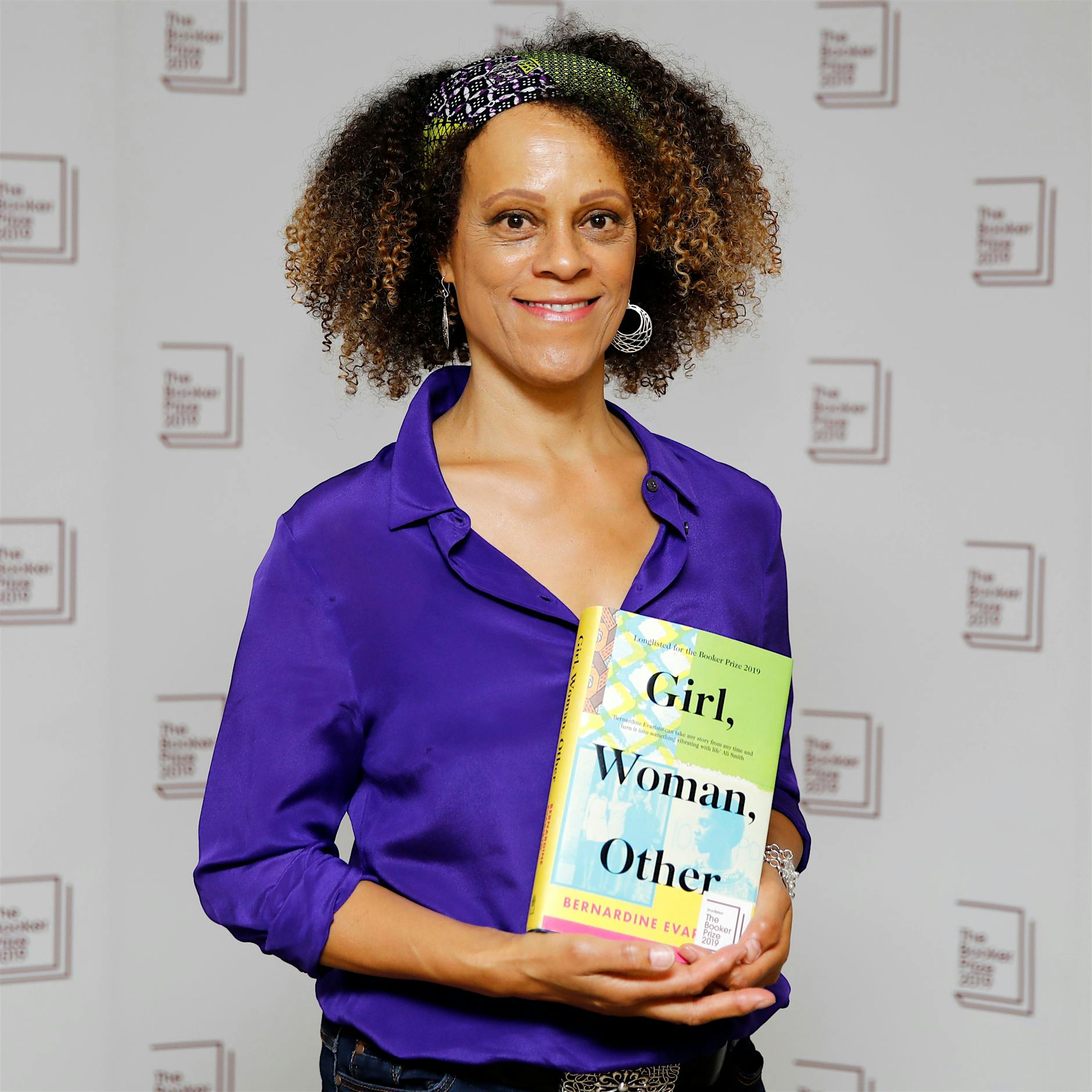

So the question remains: Should Carolin Würfel have been allowed to write about Johann König at all? She is a respected journalist, fights in her articles with good arguments against patriarchy, against ingrained structures in West German-dominated journalism led by older men, is held in high esteem by just about all her colleagues in the industry. She is a successful book author and an excellent expert on GDR history.

And yet: Shouldn't the editors have asked why she kept such a low profile in her research? Even the scene at the end of the Zeit article is told from Carolin Würfel's point of view. She quotes from a conversation at a party with König, which she was only able to have because she is Klosterfelde's wife. The scene has since had to be deleted. It is interesting because Würfel omits a detail here. The scene takes place at a party given by Jorinde Voigt, an artist that was until recently represented by both galleries: König and Klosterfelde. At the Art Cologne art fair 2022, the galleries had their booths next to each other.

Was the result of the research predetermined from the start?

In April 2019, Zeit republished its own Code of Ethics: A voluntary commitment for its journalists, who do not face legal consequences for any violations. Nevertheless, it applies to all the paper's journalists. The first sentence, item 1a of the Code, reads: "The editors of Zeit Online and Die Zeit will disclose possible conflicts of interest to their direct supervisor." Either Würfel's colleagues didn't do that, or their superiors didn't care.

But what if there are additional conflicts of interest among the publishers of Zeit? Florian Illies is one of four editors of Die Zeit, after the fifth, Josef Joffe, stepped down due to other compliance conflicts. Illies is the author of the bestselling books "Generation Golf" and "1913". He joined Rowohlt Publishing House in 2018 amid much protest from the publisher's female authors, but left the post after just one year. He was well acquainted with Johann König for a long time, not unusual for a person working for a major Berlin auction house.

Illies appeared on König's podcast and opened exhibitions. Were the authors aware of this connection? Did they not care that Illies' partner had worked for Johann König until 2020 and before that was employed at Grisebach, where Illies held a senior position and the two are said to have met? Did her resignation from Galerie König influence any reporting in the König case? On enquiry, Die Zeit writes that there was no contact between the authors and Florian Illies prior to publication.

In addition, there are text messages that show beyond doubt that the authors of the article had indeed made inquiries with several female employees and alumni of Galerie König. The answers, which the Berliner Zeitung has seen, paint a more differentiated picture of Johann König's dealings with women in his environment. However, they were not included in the text. Did they not fit into the narrative? Had the result of the research been predetermined from the start?

An indication of how much the creation of the König article might have been driven by genuine anger and a sense of injustice is provided by a particular "Piece of Art". This is the name of a script synopsis that has been made available to the Berliner Zeitung. Over 16 pages, it describes a Netflix-style miniseries. The content is revealing in many ways. It does not so much provide an insight into the world of art, but rather into the mind of the author Carolin Würfel. On the first page, a subheading reads in English: "Inspired by true events."

In seven parts, the synopsis describes the "dazzling Berlin art world" in which "abuse of power is part of daily business." There are three main protagonists in the manuscript: Elena Baum, who starts working in a Berlin gallery. Her husband got her the job; he is friends with the gallery owner. Then there's Maxi Rosenthal, "a journalist for a major German daily newspaper." The fictional Maxi's main topic is feminism. She also pursues the goal of making a case of sexual abuse of power public, "even if her editors want to stop her."

Could this be the rape she's missing for her article?

The third main character is Alexander Fürst - described as "Germany's most successful gallery owner and art dealer" in Würfel's series synopsis. Like all the characters in the plot, this one is easily relatable to reality and heavily exaggerated: "The only things that interest Fürst are conquering women and flipping artworks." Like Johann König, Fürst also has a disability. König had an accident in childhood and has had poor eyesight ever since. In Würfel's synopsis, Fürst drags his left leg after suffering from polio.

The synopsis also features ten women who want to go to the press. But from the third episode onward, the fiction deviates sharply from reality: namely, Maxi's editorial team rejects the article about the art dealer Fürst. Maxi's section editor is "an art philistine", writes Würfel, and "no expert on the scene." No one outside the cultural bubble knows Fürst, the boss says. "My God, it's just a bit of groping." Maxi turns to the editor-in-chief, who says, "I'd rather keep the paper out of this MeToo madness, which is mostly just whispers anyway." Maxi receives an official warning.

The synopsis continues: "The German press has cast Maxi out, but her fighting spirit is unbroken." Later, the two women, who become a lesbian couple in the course of the story, meet another editor who says he will print the story – if it includes a rape case. Maxi later ends up sleeping with the gallery owner Fürst at a sex party at a castle in Brandenburg. She's high and they're both wearing masks. Still, Maxi wonders: could this be the rape she's missing for her article?

People from Berlin's art world can easily recognize every person in this fever dream. In the end, the story turns violent. "Maxi only wants revenge. Retribution. NOW." The group of women carry out vigilante justice, the feminists kidnap the gallery owner, tie him to a chair and take turns torturing him. The synopsis reads: "Killing him seems like a real option, especially for Maxi." They finally administer drugs to Fürst, which he risks choking to death on. Elena ends up facing a decision: How far would she go for a self-determined life?

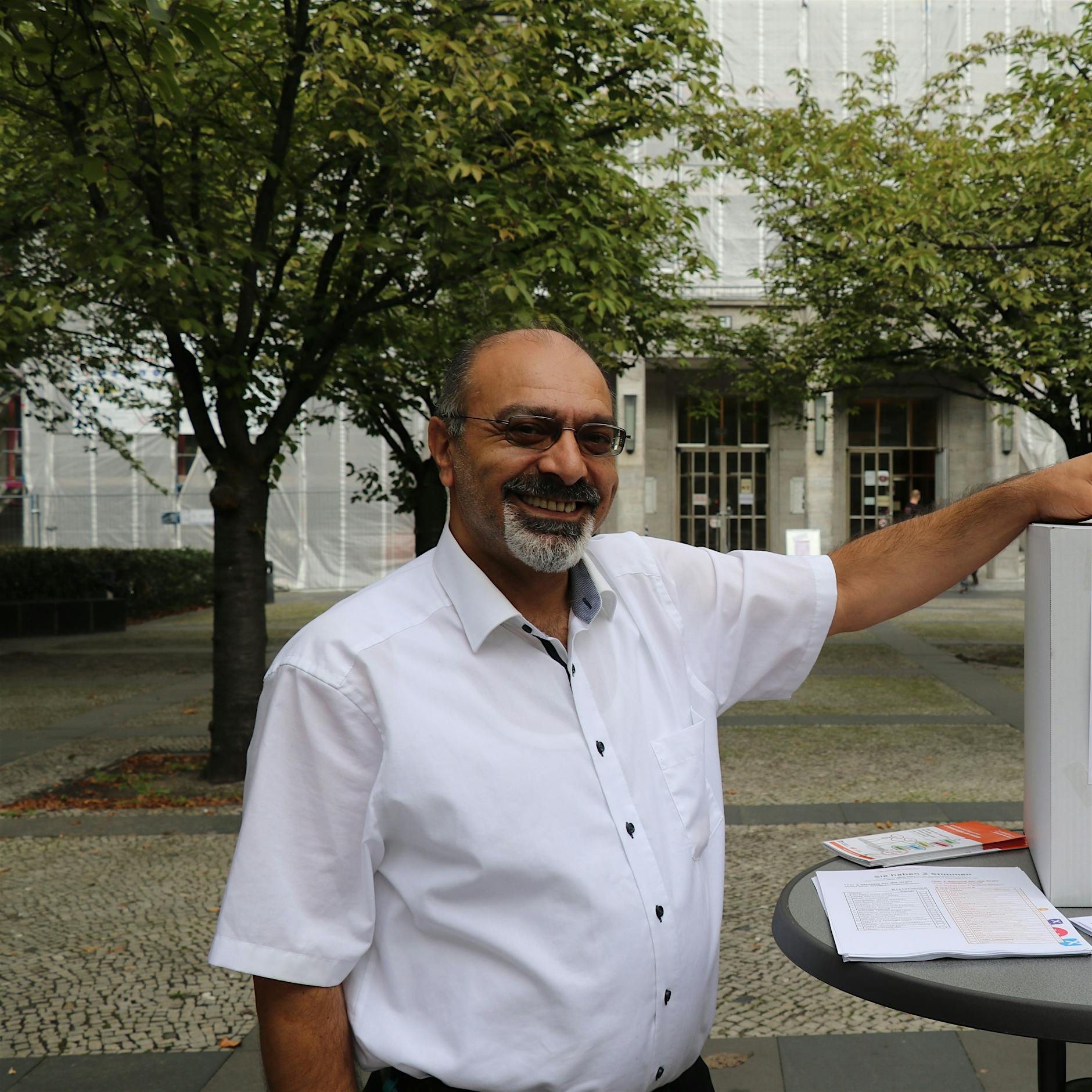

After the publication of the Zeit article in August, the gallery owner Johann König discontinued his art magazine "König" and laid off several employees. He closed the branch of his gallery in Vienna. He was disinvited from Art Basel. At the time of this article's publication, at least ten of the more than 40 artists at Galerie König have left. Jorinde Voigt also left König this week, staying on only with Klosterfelde. König, according to people close to him, has lost friendships, endured verbal attacks. For many women, however, the Zeit article offers vindication, belated justice. In turn, those close to König say he has not been drinking or taking drugs for two years. Wreaths were placed in front of the door of his gallery to denounce him, he received threatening phone calls, and an anonymous feminist network called on König's female artists to turn their backs on him.

And they're succeeding, as demonstrated this week at a special press conference in the Neue Nationalgalerie on Wednesday, 11am. Monica Bonvicini was invited to show her art behind the huge glass panes of the famous Mies van der Rohe building. She was represented by Johann König for about a decade. Some say he made her really big. Bonvicini's smile is somewhat pained despite her great success of the day. She doesn't want to say anything about the König case, her assistants make clear beforehand. But in the audience, one hears the name König again and again.

The exhibition "I do you" shows that Monica Bonvicini knows her way around that particular world of power and sex and play and coercion. There are chains hanging from the ceiling, with scraps of leather, and English words written on glass: "A failed romance", or "It was an uneasy night". They seem almost like a comment on the scandal. Next to the words, there are handcuffs that visitors can bind themselves to - "to have the experience of being at the mercy of somebody," a curator says. The largest artwork in the exhibition is a carpet on which clothing is depicted. The clothes look like carelessly discarded, maybe someone was on his or her way to bed. Or is this the evidence of a violent act? All you can see is: a lot of dirty laundry.